By now you have probably gotten used to the provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that became effective January 1, 2018. But don’t forget, most of the tax changes made by the TCJA are not permanent and will expire (sunset) after 2025. This will have an impact on long range tax planning and will result in a mixed bag of tax increases and tax cuts. How it will impact individual taxpayers will depend upon which provisions of TCJA affect them. The following is a review of what will happen when TCJA expires if Congress doesn’t intervene.

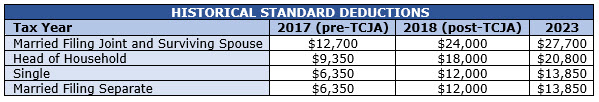

Standard Deductions – The standard deduction is that amount of deductions you are allowed on your tax return without itemizing your deductions. The standard deduction is annually adjusted for inflation. In 2018, the TCJA just about doubled the standard deduction as illustrated in the table below that also illustrates the 2023 standard deduction amounts. With expiration of TCJA the standard deduction will be cut roughly in half.

The increased standard deduction under TCJA benefited lower income taxpayers and retirees, whose itemized deductions often were just barely more than the pre-TCJA standard allowance. The increased standard deductions also meant fewer taxpayers claimed itemized deductions – roughly 10% of filers now itemize versus 30% before TCJA – which helped simplify these filers’ returns.

Personal & Dependent Exemptions – Prior to 2018, the tax law allowed a deduction for personal and dependent exemption allowances. One allowance was permitted for each filer and spouse and each dependent claimed on the federal return. For the year prior to the TCJA’s suspension of the exemption deduction, the exemption amount was $4,050, which would have been inflation adjusted to $4,700 in 2023. The deduction for exemptions phased out for higher income taxpayers.

Child Tax Credit – Prior to 2018 the child tax credit was $1,000 for each child below the age of 17 at the end of the year. With the advent of TCJA the child tax credit was doubled to $2,000 for each child below the age of 17 at the end of the year. This more than made up for the loss of a child’s personal exemption deduction for lower income families.

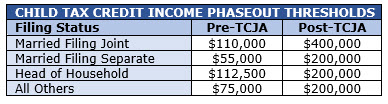

The child tax credit is subject to phaseout for higher income taxpayers. However, TCJA substantially increased the income phaseout thresholds as illustrated in the table below, so much so that the credit became available to middle-income taxpayers. Also of note is the fact that the phaseout thresholds for the credit are not inflation adjusted. As a result, each year the credit benefit is gradually diminished for higher-income taxpayers.

If the credit is allowed to revert to the pre-TCJA amount of $1,000 and the lower income phaseout levels, it will have significant negative impact on families.

You may recall that for one year during the Covid-19 pandemic, the child credit amount was increased to $3,000 or $3,600, depending on the child’s age, and other temporary changes were made. Some in Congress want to permanently bring back these enhancements, so that possibility could become part of any legislation negotiations surrounding the sunsetting or extension of TCJA provisions.

Home Mortgage Interest Limitations – Prior to the passage of TCJA taxpayers could deduct as an itemized deduction the interest on $1 Million ($500,000 for married taxpayers filing separate) of acquisition debt and the interest on $100,000 of equity debt secured by their first and second homes. With the passage of TCJA, the $1 Million limitation was reduced to $750,000 for loans made after 2017 and any deduction of equity debt interest lwas suspended (not allowed). A return to pre-TCJA levels will tend to benefit higher income taxpayer with more expensive homes and higher mortgages.

Tier 2 Miscellaneous Deductions – TCJA suspended the itemized deduction for miscellaneous deductions for tax preparation fees, unreimbursed employee business expenses, and investment expenses. Most notable of these is unreimbursed employee expenses which allowed employees to deduct the cost of such things as union dues, uniforms, profession-related education, tools and other expenses related to their employment and profession not paid for by their employer. Investment expenses included investment management fees charged by brokerage firms and tax preparation fees, including the cost of tax return preparation and tax planning expenses. These types of expenses were allowed only to the extent they totaled more than 2% of the taxpayer’s adjusted gross income.

Phaseout of Itemized Deductions – Prior to TCJA itemized deductions were phased out for higher income taxpayers. The phaseout thresholds were annually inflation adjusted and for 2017, the year prior to TCJA taking effect, the AGI thresholds were $313,800 for married taxpayers filing jointly (half that for married filing separate), $261,500 for single filers, and $287,650 for those filing as head of household. Under TCJA the phaseouts were suspended, which only benefited higher income taxpayers. If the phaseout is reinstated, it will negatively affect upper income taxpayers, and increase the complexity of their returns.

SALT Limits – SALT is the acronym for “state and local taxes”. TCJA limited the annual SALT itemized deduction to $10,000, which primarily impacted residents of states with high state income tax and real property tax rates, such as NY, NJ, and CA. Several states have developed somewhat complicated work-a-arounds to the $10,000 limits that benefit taxpayers who have partnership interests or are shareholders in S corporations. The elimination of the SALT limitation will favor those residing in states with a state income tax and those with larger property taxes.

Moving Deduction – Prior to the implementation of TCJA taxpayers were able to deduct unreimbursed job-related moving costs where there was an increased commuting distance of 50 miles or more from the prior home and provided the individual worked at the new location full time for 39 weeks of the first 52 weeks (39 weeks first year and 78 weeks in first 2 years for self-employed persons). The moving deduction for active-duty military members was not suspended by TCJA. A restoration of this deduction would benefit taxpayers who are relocating because of job change where the employer is not reimbursing the cost of the move.

Commuting Tax Benefits – Prior to TCJA, an employer could reimburse an employee up to $20 a month for commuting to work on a bicycle, the $20 ($240 annually) was not taxable to the employee, and the employer could deduct the $20. TCJA suspended that benefit for bike commuters for years 2018 through 2025. In addition, although employers can provide a tax-free benefit to employees for transit passes, commuter transportation, and qualified parking, the employer is unable to deduct those expenses under TCJA. For 2023 the maximum monthly exclusion for these fringe benefits is $300 ($3,600 annually). The sunsetting of TCJA may provide an incentive for employers to once again provide the bicycle commuting benefit to their employees.

Personal Casualty Losses – Personal casualty losses are part of the Schedule A itemized deductions. TCJA suspended these losses that did not result from a federally declared disaster. If this deduction is restored, individuals will be able to deduct unreimbursed losses that exceed $100 per casualty and to the extent that these casualties exceed 10% of the individual’s AGI for the year.

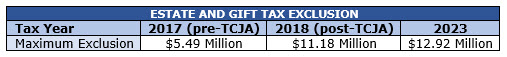

Estate Tax Exclusion – TCJA virtually doubled the inflation-adjusted estate and gift tax exclusion as illustrated in the table below. This benefited wealthier taxpayers with larger estates. Also illustrated in the table is the inflation adjusted amount for 2023.

Most taxpayers have estates well under the pre-TCJA exclusion amount and will not be affected by a restoration of the lower amounts. However, this is not true of wealthier taxpayers, especially considering the estate tax rate is currently 40%.

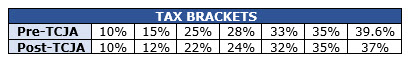

Tax Brackets – TCJA altered the tax brackets and although most taxpayers benefited, higher income taxpayers benefited the most with a 2.6% cut in the top tax rate. The table only reflects different tax brackets. They may or may not apply to the same levels of income.

A return to the pre-TCJA rates would have the largest negative effect on higher income taxpayers.

Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) – As part of TCJA Congress did eliminate the Corporate AMT, and even though they had also vowed to eliminate the individual AMT, when the final TCJA was passed, it was still there. But they did include a modest increase of the AMT exemption amounts and a huge increase in exemption amount phase-out thresholds. These, in addition to several other regular tax changes made by TCJA that eliminated certain itemized deductions that caused the AMT in the past, virtually wiped away the AMT for most taxpayers that were affected by it in years before 2018. Depending what changes Congress makes when TCJA expires, the AMT could again cause grief for many taxpayers.

Qualified Business Income (QBI) Deduction – As part of TCJA, Congress changed the tax-rate structure for C corporations to a flat rate of 21% instead of the former graduated rates that topped out at 35%. Needing a way to equalize the rate reduction for all taxpayers with business income, Congress came up with a new deduction for businesses that are not organized as C corporations.

This resulted in a new and substantial tax benefit for most non-C corporation business owners in the form of a deduction that is generally equal to 20% of their qualified business income (QBI). If allowed to sunset with TCJA, businesses (generally small businesses) will lose a substantial deduction. Of course, these potential changes assume Congress does not extend or alter them. And they aren’t the only tax issues impacted by the December 31, 2025, TCJA sunset date, but are probably those that will affect the most taxpayers. Depending upon your particular circumstances, these possible changes can potentially impact your long-term planning such as buying a home, retirement planning, estate planning, future tax liability and other issues.